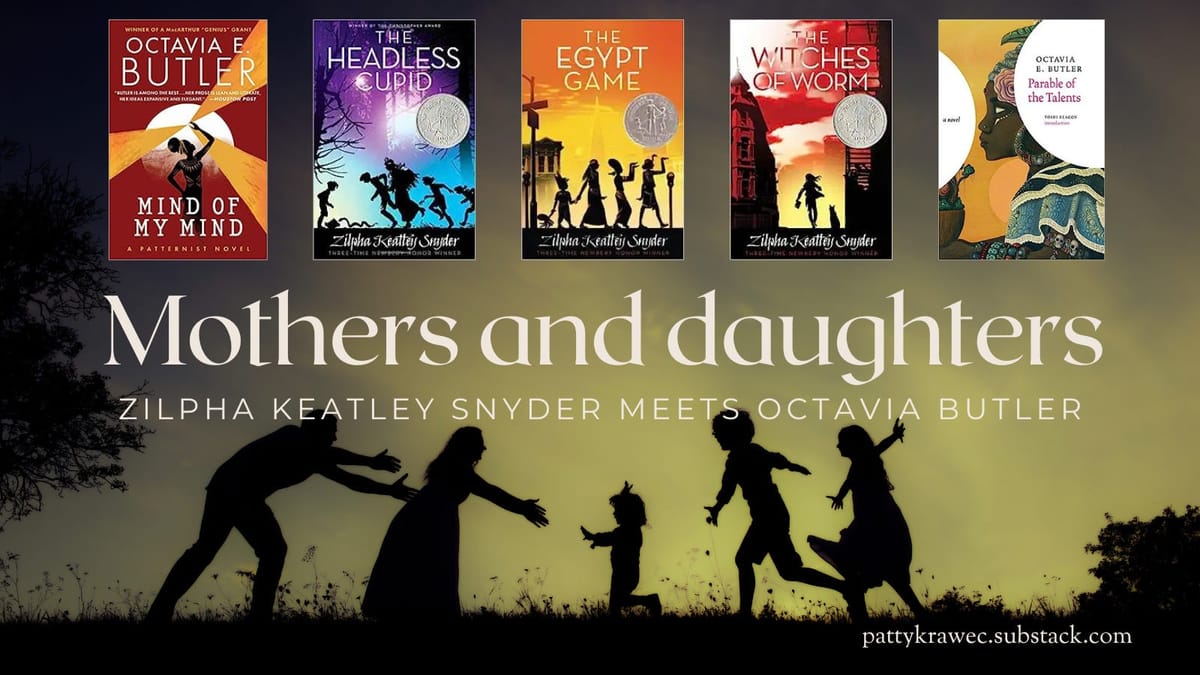

Mothers and daughters

Zilpha Keatley Snyder meets Octavia Butler

A few weeks ago somebody on the bird app asked about books we read as pre-teens, specifically she was asking about spooky books. I could not remember the author or any storyline coherently enough for a google search but I did remember the books very clearly. Snapshots anyway. Mostly I remembered the feeling of them. Yes they were spooky but also not. They kind of danced in that in between place, but unlike Scooby Doo, when the kids finally pull off the mask to reveal the person behind the hauntings something mystical remained. And I liked that. Because although I often say that I’m the least mystical Indian you’ll meet I also know that isn’t true. I’m not one for crystals and higher vibrations, but I do know that this world extends far beyond the things we can see and touch. It’s just that trope of the hyper-spiritual mystical Indian painting with all the colours of the wind that I want to dissociate myself from. So I stay stoic. Like I just got back from hunting buffalo or something.

But this question nagged at me so I hit the google machines and tried all manner of queries, most of which brought me to endless lists of RL Stine and Goosebumps. Neither of which I read as a kid and when my own kid wanted to read Goosebumps I handed him Stephen King instead. If you’re going to read scary things at least read something that is well written. I mean, that’s debatable with King. His work relies on Indian burial ground tropes and he can’t seem to end a book well but it’s still better than the other dreck.

Then I searched “young adult books 70s occult” and bam. There she was. Zilpha Keatley Snyder and her list of Newberry award winning books. As soon as I saw her name I knew these were the ones. Armed with my booklist I went to a secondhand bookstore and came home with The Headless Cupid, Witches of Worm, and The Egypt Game. Nostalgia powered time travel for $5.

The books have held up pretty well. All written in the late 60s or early 70s but they don’t feel dated at all. And The Egypt Game has a pair of Black siblings, Melanie and Marshall, who are fully developed characters in their own right, they don’t just exist as foils to the central white character as still happens all too often almost 60 years later. 60 years later. Wow. Those kids would all be in their 70s now. An interesting detail Snyder included with the little brother: they were going trick or treating and he wanted a sign. This confused April until Melanie explained that Marshall was too little to remember trick or treating the previous year but he did remember going to a protest march with their mother. So if they were going marching, he wanted a sign to carry. I remember taking my own kids to protest marches and either giving them a sign or pinning one to their coat. Once we had to go pick their father up at the airport immediately after attending a Take Back the Night march and when he asked them what they had done that night, my youngest said “some angry women thing.” We all laughed, but years later he would organize men’s discussion groups while angry women marched.

In each of these Snyder books the central character, the one poking around in the occult, has a fraught relationship with her mother and the games that these characters play offer them power in a circumstance where they feel powerless. April’s mother Dorothea (The Egypt Game) and Jessica’s mother Joy (The Witches of Worm) are largely absent leaving their daughters in the care of a mother in law or elderly neighbour and the fathers are completely absent. Amanda’s mother Molly (The Headless Cupid) has remarried and her new husband has three children. I could relate to these books in a way that I couldn’t relate to most books at that time, my father was completely absent and my mother and I lived with her parents until she remarried. There’s a kind of helplessness that goes along with inadequate representation. I didn’t see myself or my family reflected anywhere else which provokes questions that kids don’t usually have the vocabulary to ask.

Or maybe they do, but nobody asks them what they think so they don’t say anything. When I did social work I got into the habit of asking my racially marginalized clients about how they experienced their neighbourhood or their school. It was awkward at first, more for me than for them. They had a lot they wanted to tell me but nobody ever asked them. Like the little guy who hated Scooby Doo because all the characters are white except for the dog. Or the older boy who saw how older women held their purses a little tighter when he walked by. Or my friend who recalled cashiers dropping change in her mother’s hand rather than touching her. Snyder’s books are an imperfect representation, but I still felt seen in a way I didn’t feel anywhere else.

I’m also reading Octavia Butler this year, so it’s not surprising that she’s popping up again in another essay. She’ll keep doing that. What I’m thinking about is the relationship between mothers and daughters that exists in so many of Butler’s works as well as in Snyder’s. Butler writes complicated, problematic mothers whose eye is so focused on broader issues of justice and world building that they don’t leave a lot of room for their daughters. Think Lauren Olamina founding a new religion or Lilith and Mary who found entire races. Worldbuilding is hard work, but so is any kind of work that is done in the isolation of single mothering. It requires a singularity of focus that may leave children feeling powerless. Snyder’s children turn towards the occult as a strategy of power, but Larkin (Parable of the Talents) turns towards Christianity for the same purpose. Perhaps, feeling powerless within their mother’s world they are simply turning towards something outside of it.

I think a lot about relationships of power, because one consistent feature of reconciliation is the relinquishment of power by the one who holds it. Lilith is herself powerless, but Lauren and Mary are not, nor is Anyanwu, the shape-shifting healer of Wild Seed. They either cannot or will not relinquish power which maintains the distance between them and their children. Distance and resentment. Those who live beneath the power of another will inevitably chafe at it, building resentment and finding a way turn against it. Women march in darkened streets to assert their right to be there. Indigenous people build encampments and tiny houses to block development. And others look for power through magic or religion or political office.

The trick is, and Butler’s books all deal with this in some way, not to simply replicate those patterns when you achieve power. That’s what Mary struggles with in Mind of My Mind. She knows first hand the damage done by Doro and Anyanwu in their attempts to build a race of telepaths, but she too relies on coercive control. Is it any better just because she tries to be more benevolent? Can you be a kind master to those whose service is unfree? Christianity has this problem too, because no matter how benevolent or kind your ruler is they’re still your ruler and the power imbalance forms walls that render you unfree.

I find myself persistently turning towards Anishinaabe ways of knowing and governing ourselves. That principle of non interference that runs so deep in many of the tribes who lived here long before Europeans came to stay is a relinquishment of power. Many tribal groups have mechanisms that prevent power from remaining in anyone’s hands for very long, and as my oldest says of the anarchistic tendencies of the Anishinaabe: if somebody is being a jerk about it we’ll just wander off and find somebody else to listen to. For anything to truly change it is the ones who hold power who need to relinquish it. That’s the trouble with the insistence on non violence as an ideology for protest. If the powerless are the only ones relinquishing power, then nothing will change and those in power remain unthreatened with no motivation to change the things that need changing. No wonder they like and promote non-violence. But non-violence is a strategy that provokes and exploits the violence of the state, so in that sense it does use violence to achieve its goals. Do you think Martin Luther King did not know that the police would come with batons and dogs and that this would not play well on the evening news?

They killed him anyway. So don’t talk to me about non violence.

Snyder’s mothers all relinquish power in some way. They stop insisting on their own way of doing things and their daughters are heard. Butler’s mothers are more resistant to this, perhaps because Snyder is writing for children and Butler is not. Butler knows that the powerful don’t easily give up what is theirs, particularly when they are convinced of the necessity of their vision. Maybe they are right, maybe their vision is critical to survival. But I’ll leave you with a line from Admiral Adama in Battlestar Galactica. It is not enough to survive. We must be worthy of surviving.

So say we all.