Getting unstuck

Hello there.

Today Nanaboozho gets himself a caribou, or maybe a bear. The wolves eat his kill because he got stuck in a tree, then he gets his head stuck in a skull, and while he's stumbling around the forest he bumps into various trees who answer his question "who are you?" by telling him where they grow. Which is a very interesting way to answer that question.

Today's story from William Jones is Nanabushu and the Caribou with accompanying context from Tales of Nanabozho by Dorothy M. Reid (Nanabozho and the Birches) and Isaac Murdoch's The Trail of Nenaboozhoo (Nenaboozho and the Poplar Tree and Black Spots on the Birch Tree). These come from three different eras and two different places within Anishinaabe aki. Jones and Reid both documented stories in the Thunder Bay area before it was actually Thunder Bay. Jones in 1906 and Reid in 1963. Jones was a member of the Sac and Fox tribe, studying anthropology under Franz Boas. Reid was born in Edinburgh, became the head of the Fort William public library in 1956, and hosted a weekly story program on CKPR. Her book won the Book of the Year Medal of the Canadian Association of Children's Librarians in 1965, the year I was born. Fort William amalgamated with Port Arthur, where I was born, in 1970 and that's how these places became Thunder Bay. Murdoch, who published in 2019, is relaying stories he grew up with and heard from elders in Serpent River, Ontario which is almost a thousand kilometers from Thunder Bay. These authors are pretty much on opposite ends of Lake Superior, although Serpent River is a little ways down the TransCanada Highway from where Lake Superior ends and Lake Huron begins.

This is interesting to me because it gives us a little bit of context to these stories and the differences between them, differences that are largely about emphasizing various aspects of the story or the place where it is told. If you scroll down to page 72, a Can Lit journal issue from 1964 offers a less than flattering review of Reid's book. It's not flattering to Reid, whose writing style leaves something to be desired according to the reviewer, and not particularly flattering to Indigenous people in general or the Ojibwe in particular either. She echoes "the unsubordinating, arbitrary manner of many Indian sources" and Nanaboozho himself is an "exciting superman of legend .... part hero, part rogue, part clown, as the Indians conceived him."

Bleah. I was actually hoping to find out more about Reid herself in this review but it didn't say anything at all about her. It did, intentionally or not, tell us some important things about how Native people were seen in the 60s though. Prefacing the reviews, the writer says that "their variability, the archaic symbols in their stories, and the anomalies that crept into those stories through countless retellings are not the least of the problems an adapter faces..."

Not the least of the problems.

But I love the anomalies. I love the variability. This acceptance of complication and variability would do readers of the Bible a great service by giving people an opportunity for more expansive reading rather than the straightjacket of an innerant, univocal text in which some things make absolutely no sense if you are forced to take them literally. I'm not going to go any further into the book review, you can read it for yourself, but I do want to take that context into consideration when we look at Reid's version of events. And while we're thinking of context, it is also worth noting that Franz Boas, the son of German Jews, was known for pushing the field of anthropology away from European exceptionalism (something a descendant of Jews would have some feelings about no doubt, even well before Hitler) and scientific racism and towards a more egalitarian look at cultural variation. It's not perfect, but it was a move in a more useful direction. Clearly Reid and the writers of that review did not get Boas' memo.

All this and I haven't even gotten to the story yet.

So, Nanaboozho is walking along minding his own business as he does, and he sees a great big caribou. How can I get me some of THAT he wonders, and while talking up the suspicious caribou he spins a story about a nearby village where everybody was killing each other and they were shooting each other with arrows that they strung together just like this, and he strings up his own bow. Wide-eyed with anticipation caribou asks "then what?" and Nanaboozho shoots him with the arrow.

"Dammit Nanaboozho. That's exactly what I thought you would do," and with that the caribou keels over.

Idk why caribou was so shocked. Nanaboozho practically told him what he was going to do by telling that story, but sometimes our curiosity gets the better of us. Nanaboozho sets to work processing his kill and there's some back and forth with himself about where to start eating and what his loves would say about him depending on how he chooses. In this story, Nanaboozho is very worried about being laughed at. He puts some rendered fat around the bottom of a nearby tree and when some wind gusts pick up causing the trees to rub together and creak. He wonders if somebody up there also wants to eat and climbs up with a fatty piece he wedges in where it is creaking at which point he gets stuck just as some wolves come along and eat everything.

After the wolves are gone he surveys the damage and decides to shape shift into a little snake so that he can get all the bits inside the skull except that he accidentally shifts back to human form too soon and gets the skull stuck on his own head. This is where he starts banging around the forest and every time he crashes into a tree he says "who are you?" The trees respond by describing where they are and he says oh you must be a pine or a tamarack or cedar or birch, depending on what they tell him. From the trees' answers he is clearing moving towards the lake and eventually he winds up in the water. Some Anishinaabe see the antlers and think he's a caribou swimming across the lake, but he's too far away for them to hunt. He stumbles up onto the shore and falls, cracking the caribou skull on some rocks which gets it off his head and he continues on his way.

I have no idea why the story takes the time to tell us that Nanaboozho put the rendered fat at the base of a tree, and I did ask the google machines which gave me 10 uses for animal fat in the wild. An interesting article to be sure, but Idk. Maybe it was an offering to small animals that live in the forest, a lot of composting articles advise against composting animal remains (from meals or otherwise) because it will attract rodents so maybe that? I have no idea, but I'm inclined to think it was a kindness to small forest creatures who like such things. In Reid's version she says that it is autumn, so perhaps this was a kindness to animals who would need to bulk up a little before winter. That fits with his response to the creaking he hears, the assumption that somebody (perhaps the tree itself) wants some of what he's got. This is at odds with Reid's story that presents him as violent and greedy, a good example of the difference between us telling our own stories and others telling our stories for us.

Reid's version has Nanaboozho killing a bear and instead of tricking it he sings a song of apology (I'm hungry, need your fur for winter, please don't hate me) and the bear is too drowsy to do anything but stand there while Nanaboozho hits it repeatedly with a tree root. In this story the creaking of the trees mocks and scolds, seeming to call him a "greedy fellow" which sends him up one of the trees in a rage and he gets stuck. The wolves appear, pretend not to see him up there, eat everything, and when Nanaboozho gets down he is so mad he takes the boughs of a willow tree and whips the birch with them creating the marks.

I mean, none of these things are particularly out of character for Nanaboozho. He can be greedy and reactive, but it is definitely at odds with the song that he is singing. The song bothers me, because although it's true that there are songs and offers of thanks for the animal being hunted there's something about the way that this is presented because of the violence and accusation of greed. There isn't anybody else around for him to share it with anyway so why, after he sings this song about gratitude, are the trees assuming he's being greedy?

And there's the matter of the drowsy bear. At least the caribou had some agency, it was rightly suspicious but then drawn in (as many others are) by Nanaboozho's promise of a story. The bear just seems to be a helpless, drowsy victim while Nanaboozho bludgeons it with a tree root. Once again, that disconnect between the song he is singing and his actions which makes me think about how Native people are simultaneously super-spiritual but also savage and dangerous.

Something similar shows up in Murdoch's story about the Black Spots on the Birch Tree, but it isn't in the context of a hunt and getting stuck while wolves eat his food. And it isn't because he's mad at the birch for spoiling his meal. Birch tree is kind of a jerk, telling the spruce that on Wednesdays, we wear pink and that is the ugliest effing bark I've ever seen. OMG, Nanaboozho says, calling someone ugly is not gonna make you better looking. I’m sorry that people are so jealous of me, but I can’t help it that I’m popular, Birch sniffs at which point Nanaboozho grabs a spruce bow and starts smacking birch leaving those little marks on it, and it was never mean to another tree again.

Poplar on the other hand hides Nanaboozho while he's on the run and in gratitude Nanaboozho puts his eagle staff inside the tree, giving it a heart and the name Zaade. Murdoch goes on to note that Ojibwe use poplar in ceremony and that the crutch in poplar trees, the split trunk that is frequently seen, is where the old lady is waiting on the path of souls. The tree, he says, is connected to the stars because of the power Nanaboozho left behind and when you look at their leaves from the bottom they do twinkle like stars.

Looking at images of poplar and birch I'm struck by the similarities. Even the bark of some poplars has a similar patterning to birch, although only birch bark peels away in that distinctive way. Almost like it's trying to make up for being such a jerk by providing bark that can be used for baskets and whatnot without having to actually take down the tree.

Birch is stronger and harder than poplar, which is why we made birch canoes. You can also make syrup from the sap of a birch tree, which has a lot of medicinal uses including being very good for your skin. Poplar (particularly quaking aspen) can be a firebreak during a wild fire, depending on what else is around them and the state of the forest itself. And of course poplar buds are a staple ingredient in minigan because they contain salicin, a painkiller, along with microbial and anti-inflammatory properties. These trees are pretty amazing, and which one is better depends entirely upon what you want to do with it.

As he's crashing around the forest, Jones' Nanaboozho encounters several trees, including a birch and a poplar. He asks each of them "who are you?" and their responses '"I'm on the mountain" "I'm near the lake" "I'm right at the lake" help him navigate his way to the water. That is kind of interesting to me. He asks "who are you" and each of the trees answers with their location, which is kind of what Anishinaabe do when we give our introductions. We give our names, and then as we expand outwards we give our location socially and geographically, the people and places we are from.

This is something that a lot of people do, it isn't uniquely native (my German grandmother did this all the time to find people she may have connection with) and it isn't "protocol" which is something I've heard a lot of people say, mostly to justify their own intrusive questions about somebody's pedigree so they can assess their legitimacy. Yes, yes, frauds are a problem. People make claims about relationship that they simply don't have and that's bad. But so is this aggressive questioning that assumes everybody knows all the things. Sometimes the cure is just as bad as the problem it pretends to solve, which tells me that it really isn't about solving that problem at all.

Back to these trees and their introductions.

Giving your position, your relationship to people and places, helps a lot with understanding the context of our words but it is mostly marginalized people who do it and what if your need for context isn't the only point? What if it's simply the desire to be seen for who they are. They explain their race or their religion, they explain where they are from because they want their audience to have that context for their words and they want to be seen. When I read a novel and it's written by a native author, it doesn't just give me context. It ensures that I see them rather than just going with the typical assumptions.

White, Christian, straight, male. None of these things are an invisible default position but that is exactly how they operate. Think about a piece of fiction you read recently and consider one of the characters. How do you imagine them? Because unless the author tells you otherwise, chances are you imagine them as white and this isn't just because we're imagining them to be like us. Racially marginalized people do this too. Unless we are told otherwise, we assume that the character is white. We do the same thing with authors, unless we are told otherwise we assume that they are white. Exceptions of course being people with names that are categorized as not from here.

One of the things that settler colonialism does, is that it disconnects us from our own history, and in doing that it disconnects us from each other. From people and places. Thinking about your relationship to people and places is one way to refuse that disconnection. To think about who your parents and grandparents were, how they got here and what made it possible for them to do that. What's neat about this story is that by answering this way, the trees helped Nanaboozho orient himself. It didn't just provide context for Nanaboozho to hear their own stories, the way that I provided context for Jones, Reid, and Murdoch at the beginning of this newsletter, the trees weren't telling stories. Their responses helped him navigate the forest when he couldn't see because of the skull stuck on his head. They could have said "oh I'm a tamarack" and he would have known where he was because he knew where tamaracks grow, but they didn't do that. They responded by saying where they were. And yes, it helped to teach the listener about where these trees grow, but that lesson could have been taught by them giving their name and Nanaboozho explaining where they were. "I'm a spruce" "Oh! you grow on the mountain."

How would identifying our relations to people and place help others orient themselves when they are similarly stuck? Because stuck is a problem of location, and stuck is why those wolves ate Nanaboozho's dinner. Stuck is an ongoing problem in this story, but so is getting unstuck. How does that kind of response from others help us orient ourselves when we feel stuck? Nanaboozho is not like the trees. He did not hear their response and think "yes, this is where I belong, I am like this too." He heard their response and continued on his own journey, their answers helping him orient himself towards that goal.

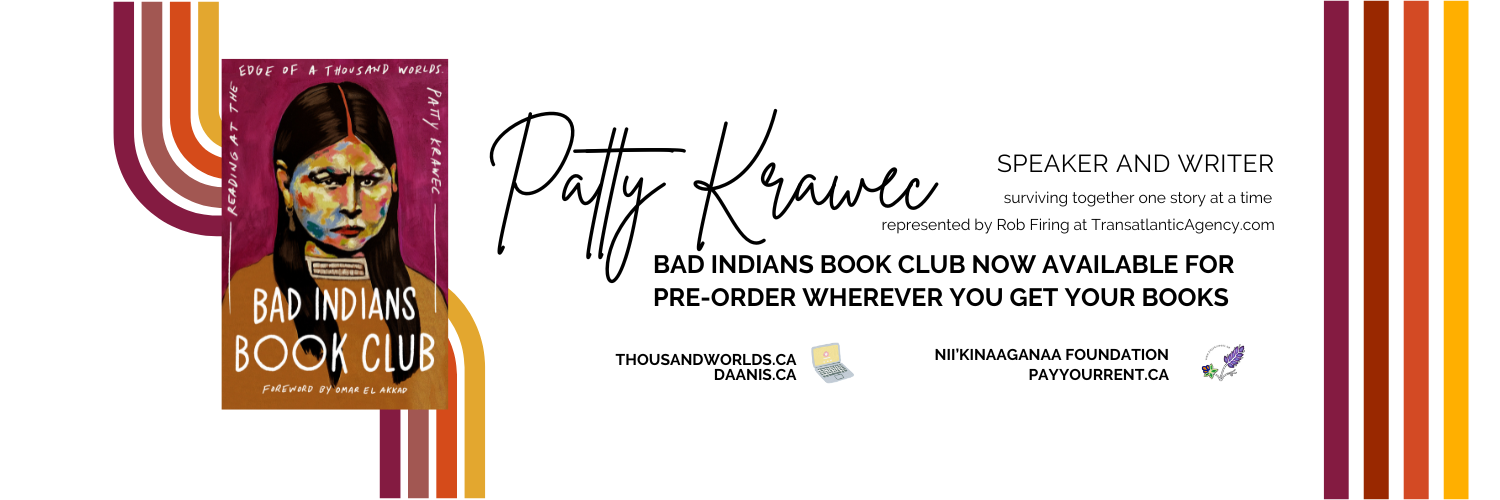

In Bad Indians Book Club: Reading at the Edge of a Thousand Worlds I identify everybody I cite or reference by their location, a practice I picked up from Max Liboiron in Pollution is Colonialism. The point of my book is to challenge how we orient ourselves as readers, to use these markers to help us read differently or more intentionally, to see what those who are located differently may have to teach us as we move towards our own goals. Look at your own bookcase, the youtube videos you watch, and let the location of the authors and speakers tell you something about your own location, about where you currently are, and ask yourself if this is really where you want to be.

Might help you get unstuck.

Today I'm thinking about books that helped me get unstuck.

Beginning Again: Stories of Movement and Migration in Appalachia edited by Katrina M Powell. This was part of the Haymarket Books book club, which I keep recommending. For a while I was getting one hard copy each month (now I get all electronic) and I used that to choose a book on a topic I didn't know much about which is how I wound up with a book about Appalachia a few weeks before Trump picked his running mate, the author of Hillbilly Elegy. Beginning Again is a surprising book because it showed me stories from an Appalachia I did not realize existed. One that is diverse and about as far from the stereotypes of Vance's book as you can get.

Talking about stereotypes, Praying to the West: How Muslims Shaped the Americas by Omar Mouallem also contained some real surprises. Things that I kind of knew but didn't think about, like the fact that Muslims have been here as long as anyone else. They came with the first enslaved Africans. They came as traders and businessmen. They've been here for as long as there has been an America. Mouallem explores this history through the stories of mosques throughout the Americas and it is not a single story. Islam is much more diverse than we know. And talking about diversity within Islam, may I also recommend Islam and Anarchism: Relationships and Resonances by Mohamed Abdou. The title alone will get you unstuck, Abdou invites us to a vision of Islam that is certainly at odds with how it is typically presented and perceived in media.

Unsettling the Word: Biblical Experiments in Decolonization, edited by Steven Heinrichs is an interesting collection of essays in which Indigenous and Settler authors re-imagine these old stories towards a liberatory, reparative future. We don't have to read the Bible the way that we do, it doesn't have to justify all the harms being done with the way the stories are read and told. There are a lot of different readings and traditions, let this one get you unstuck from the ones that are holding you in a narrow, confined space. And while we're thinking about the Bible, The Pharisees edited by Amy-Jill Levine and Joseph Sievers, is a fascinating collection of essays on a group we often get stuck on but actually know very little about other than using them as a synonym for greedy hypocrites. Stop doing that.

A Theory of System Justification by John Jost is for those of you who like to nerd out on social theory and why we do the things that we do. In this case, the question is why do we defend and embrace oppressive systems, even when we're the ones being oppressed. It's all psychology and social theory and if that's your thing you will love this book about why we stay stuck.

Finally, recommending 78 Acts of Liberation: Tarot to Transform Our World by Lane Smith again. Whether or not you practice Tarot, this book is one of an emerging tradition that reads Tarot in a liberatory way, seeing in the various cards and their relationships to each other a possiblity for collective change rather than purely internal transformation. From what I understand, Tarot is fundamentally about getting unstuck, helping us identify patterns in our lives and finding a pathway out of the places where we are or feel trapped. Taking that and expanding it to the systems we live in is a brilliant turn, and Smith isn't the only tarot practitioner making this shift.

And don't forget to join up with the Nii'kinaaganaa Foundation. Every month we collect funds from people living on Indigenous land and redistribute them to Indigenous people and organzers. You can find out more information on the website which is now powered by ghost, which means that you can become a subscriber there just like you are here!