The marble fireplace was supported by blackamoors of ebony; the light of the gas fire place played over the gilded rose-chains which linked their thick ankles. The fireplace came from an age, it might have been the seventeenth century, it might have been the nineteenth, when blackamoors had briefly replaced Borzois as the decorative beasts of society.

John le Carré, The Looking Glass War. Cited by Ruth Wilson Gilmore in Decorative Beasts: Dogging the Academy in the Late 20th Century, published in Abolition Geographies.

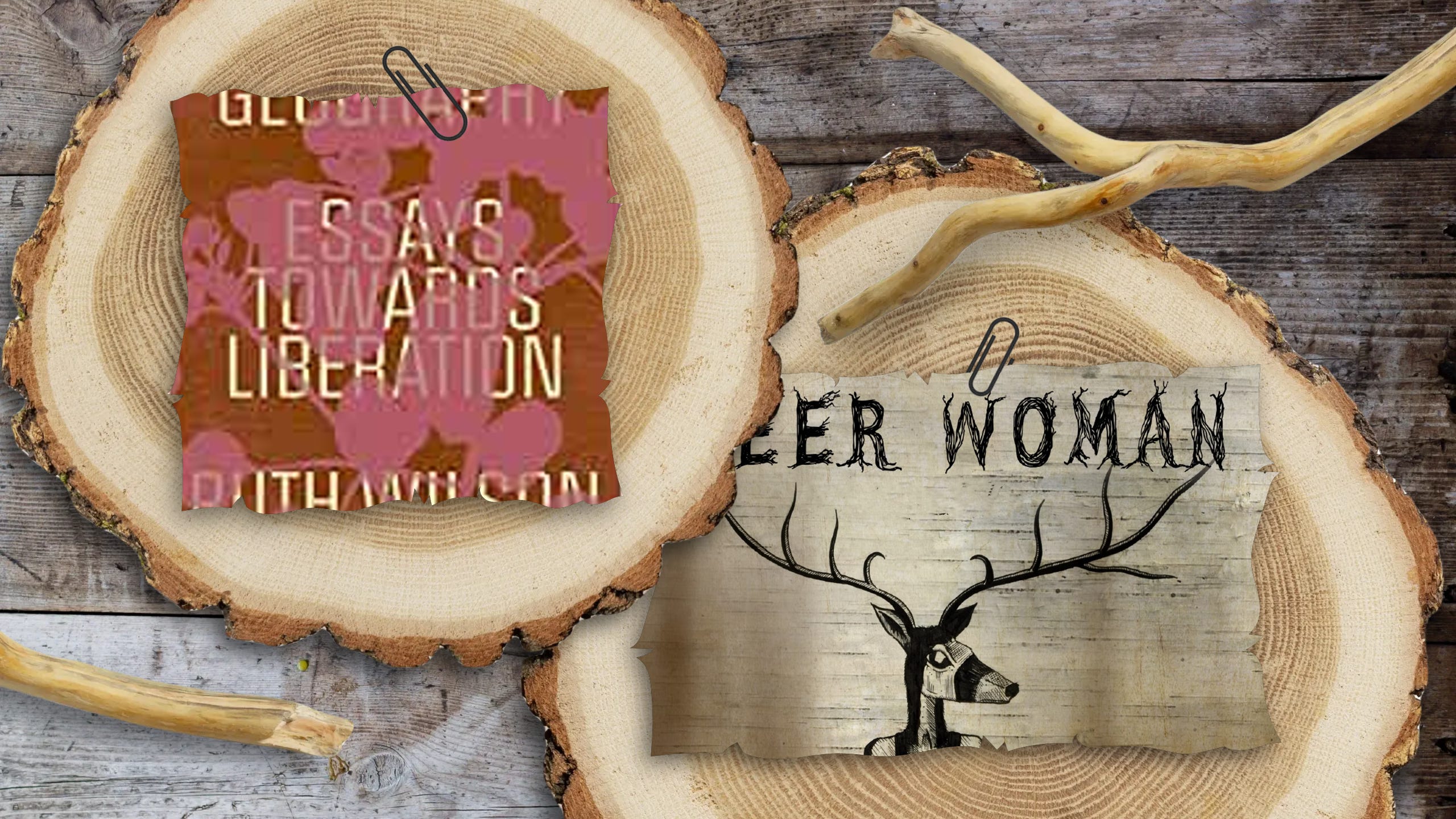

I’ve been thinking about Deer Woman a lot, and not just because she showed up in Reservation Dogs. Maybe it’s the antlers that Hela wore in Thor: Ragnarok and her complicated villainy that got me headed in her direction. Because as an aside? While I understand the villainy of Hela and the Scarlet Witch I am also sympathetic to them in ways I am not sympathetic to other villains.

I’ve been thinking about Deer Woman and who she is; the only stories I’ve heard about her are stories about vengeance and retribution and in that complicated villain way I was sympathetic to her too. I knew that there was violence in her story that provoked the retribution and but I also know that when we go down that road the innocent get caught up along with the guilty. Which is part of why I’m an abolitionist. I don’t want to live in a world that is so willing to punish the guilty that we are ok with a little bit of collateral damage.

So I asked a friend who knows these things if she knew any stories about Deer Woman. I’d asked the google machines but honestly, it’s better to get these things from a friend. As it happened she wanted a ribbon skirt and so I traded a ribbon skirt for a story about Deer Woman. This is, with embellishments and some writerly license, what she told me.

There is a story of a kwe, a young woman or girl, who was fleeing harm and in her flight she ran deeper and deeper into the woods. Branches scraped her arms and face, bugs bit her. In this way the forest warned her against this path and still she ran, fleeing the danger behind her. She stumbled, wrenching her ankle and got back up. Despite her injury she kept running until she fell again and and again until she could not get back up. As this kwe lay on the forest floor, she knew that these breaths would be her last and so she spoke to Creator. She spoke of her gratitude for the life she had, the people who cared for her, the generosities she had known. The warmth of the earth in her hands and the smell of pine around her. She wept her gratitude into the forest floor.

A doe and her fawn were nearby, and the fawn was so moved by this kwe’s gratitude that she left her mother to lie beside her. Understanding that her fawn did not want this kwe to die alone, the doe left them in this small clearing. The fawn curled up beside kwe, sharing her own warmth with that of the young woman or girl. Her hand reached for the fawn’s foreleg and together they slept.

Perhaps it got cold.

Perhaps it rained.

Perhaps the doe was delayed in returning.

The fawn and the kwe died that night and in that shared death their souls were combined. And from that shared death, Deer Woman rose and began to walk the land.

Deer Woman is an old story, it is a story of compassion and care in the midst of danger. It is also a story that has evolved and changed. Newer retellings of this story contain themes of retribution and violence, punishing those who merit punishment. The seeds of this evolution are contained in the story itself. The kwe is fleeing something, some unnamed danger and although the forest warns her against the path she is taking by putting obstacles in her way she persists, fearing the danger behind her more than the warnings.

Other seeds are present too. A doe does not typically have antlers, it’s the result of elevated testosterone which some may see as an abberation or a flaw but the Ojibwe understand in the contemporary parlance of two-spiritedness. A Mohawk woman I know talks about carrying male and female energy which is another way to understand it. The way we construct family shapes the way we construct gender and sexuality, and the family that was imposed over our communities caused a lot of harm that Deer Woman helps us to push back against.

Later evolutions of this story render Deer Woman as a temptress. In Reservation Dogs, that FX series created by Maori director Taika Waititi and Seminole filmmaker Sterlin Harjo, there is an episode that includes Deer Woman. According to a popsugar article, this depiction of Deer Woman is a “total badass” and a “dangerous being who seduces men, typically adulterous or promiscuous men, and leads them to heartbreak or death.” 1 And yet while this may seem like an empowering evolution, it also plays into dangerous tropes about the sexuality of Indigenous women.

Our stories are old, but they are not static. They live amongst us and evolve in response to the changing needs of the communities they emerge in. They come up against the stories of other communities, sometimes hidden within the colonial narratives that get inscribed on top of them. New genres, new ways of telling and hearing stories come into being as we tease out the words of our ancestors along with the new growth. These evolutions can both reflect elements of the story itself as well as the new worlds with whom our stories are now in relationship, which brings me to the idea of Deer Woman being a decorative beast.

She is everywhere, leaving her hoof prints across film and literature. Stephen Graham Jones wrote The Only Good Indians which is a tale of vengeance and arguably a Deer Woman story, or rather Elk Woman. in 2005 John Landis directed an episode of Masters of Horror about a murderous deer woman. Monster High had Isi (Choctaw for deer). Rebeca Roanhorse wrote a short story about her called “Harvest” in the New Suns: Original Speculative Fiction by People of Color anthology. And there is of course the 2017 Deer Woman anthology published by Elizabeth LaPenseé. She’s a global figure, showing up in cultures wherever there are deer-like creatures, the idea of a powerful, antlered woman is both transformative and transgressive. She’s a complicated hero, a sympathetic victim. And like the Decorative Beasts of Gilmore’s essay she rises at particular moments when it becomes possible to “instigate insurgency and provoke transformation.” 2

Gilmore is talking about the academy and the presence of the variously marginalized workers within it. They may be diversity hires, chosen to check a box or meet a need that has everything to do with the needs of the academys, but if they can survive the drought they will be in place to meet the needs of the students, the world around them. She writes about crises, those windows of opportunity that come along and cautions us that the windows to not remain open indefinitely.

Crises are inevitable. Our responsibility, as Decorative Beasts, is to be ready.

It doesn’t take a great leap of imagination to see that there are multiple crises on as many sides as there are communities vying to authority.

Gilmore talks about the discursive power of our diasporic condition, the practice of forming and reforming relationships, the new learning that emerges like Deer Woman. Wandering and walking the world she has learned much. She has met cousins, like the caribou, whose women are always antlered and ready for battle. Like the reindeer who are caribou by a different name. We enact and embody the changes, moving things from the theory where we have held them pending opportunity and into action.

We are in one such moment, and Deer Women, those decorative beasts, are coming.

Deer woman is a Decorative Beast

And how stories evolve to meet, reflect, and challenge our needs